Having the right headsail for the job is important. Quantum’s Chris Williams helps demystify the different types of headsails and when to use them for optimal performance.

Depending on the type of sailing you’re doing, be it racing, cruising, or some combination thereof, your choice of headsails may differ. Likewise, if you usually sail in areas with heavier air, lighter air, or flatter water, your optimal sail shape may differ from crew who regularly sail in choppier water. The design of your boat, whether mono-hull or catamaran, will influence your best headsail options, too. Deciding on the best sails for a yacht also involves an understanding of the differences between a genoa, a light jib, and a #4 jib. Then add in consideration of downwind sails and reaching sails. It is important (and necessary) to step back and understand the purpose of each sail type and its optimal use. In this series of articles, we will explore the design and use of the range of headsails available.

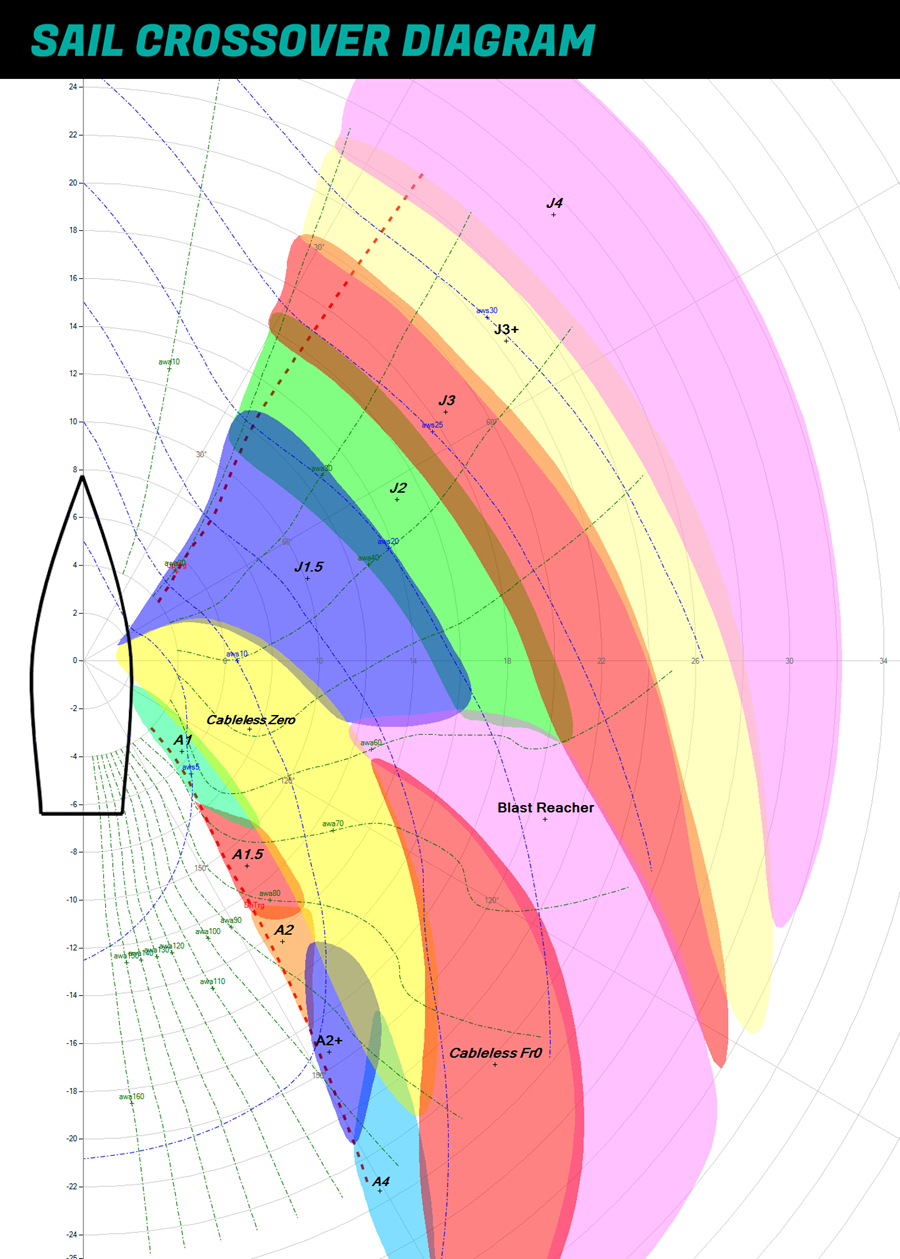

We can divide headsails into three specific groups: upwind sails, downwind sails, and reaching sails. Upwind sails optimize lift at the tightest angles to the wind; reaching sails optimize driving force across the wind; and downwind sails optimize drive when in “push mode.” Understanding how air flows across the sails in each situation helps to explain why sails are cut and sized differently for those conditions. If you’re racing, you will be constrained by class rules and/or the need to be aware of your boat’s rating relative to your competitors’. Even if you are not racing, understanding the differences in sails will help you optimize your inventory for the kind of sailing you do.

UPWIND HEADSAILS

The ability to create lift through efficient sail shape is the essence of an upwind headsail. As with the mainsail, lift is generated when the camber, or the curve of the sail, creates smooth but differing air flow speed on the windward and leeward sides of the sail. In different apparent wind speeds and angles, different sail sizes and shapes will be needed to keep the boat at its optimal angle of heel and speed. As a general rule of thumb, deeper sails create a driving force component that is more aft (lower lift/drag ratio), and flatter sails create a driving force that is angled closer to the wind (higher lift/drag ratio). All sails create some drag that pulls the yacht sideways which the keel must counter. Balancing the amount of side force versus driving force is the secret to a well-designed sail.

When rating isn’t an option, you can sometimes combine a few upwind and reaching sails for more options and better performance. When racing, upwind headsails are limited in area to keep a yacht’s handicap rating from becoming too high. As a result, sails are smaller than you would like for lighter winds. This usually prevents upwind sails from being good reaching sails in lighter conditions.

Upwind headsails go through a narrow range of apparent wind angles, but they see the greatest change in apparent wind speed of any of the sails. Because of this change, what works best in five knots of wind speed will not be your best sail in 25 knots of wind speed. In a perfect world, yachts would have multiple rigs, much like windsurfers or 18-foot skiffs, and these rigs would have sails that are appropriately sized with depths for optimum performance in a given wind speed. But we don’t live (or sail) in a perfect world, so all yachts go through a transition upwind from being underpowered to having too much sail area. The result is that you will need to find ways of increasing power with smaller sails and then reducing sail; the ability to change headsails is the most efficient.

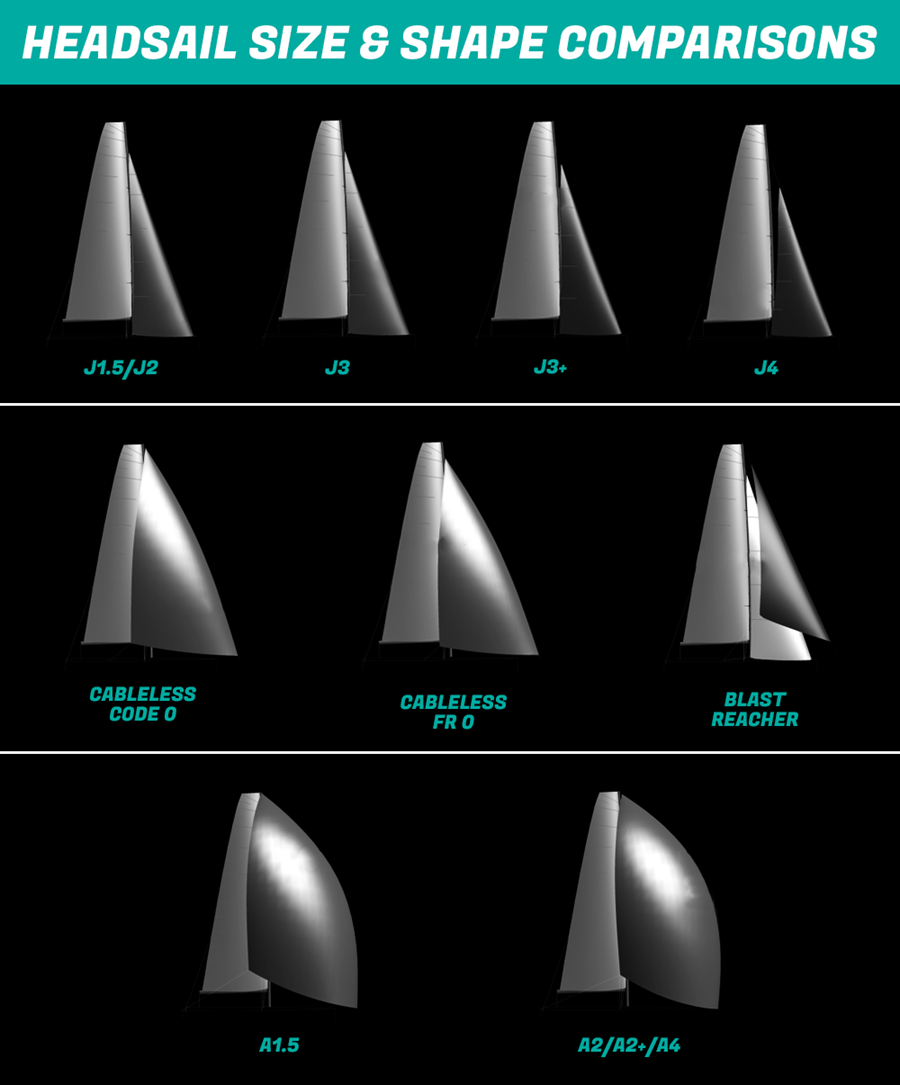

If your sail is large enough to overlap part of the main sail, it is called a genoa. Light genoas, or G1s and Number 1s, are designed to be deep and powerful in lighter winds to maximize drive even at the expense of added drag and side force. Most modern yachts now have jibs only. Similar to a Number 1 genoa, the lighter jibs are designed to produce as much power as possible. Because of this, as the wind increases, these sails become too powerful, creating too much side force, and you need to flatten the sails. Usually you can still have an efficient sail shape at maximum area; this is your J2 or medium jib/genoa. Once the wind speed increases, you cannot flatten a sail enough while maintaining efficiency, and you must reduce sail area. Some yachts will have several heavy air specialty sails that get smaller and smaller. Most yachts with genoas will then switch to jibs. These are generally your J3, J3.5, J4, and J5 jibs. As the numbers increase, the size of the sails decrease.

REACHING HEADSAILS

Now that we understand why upwind sails have different sizes and shapes from sails trying to go downwind, what happens when you want to sail across the wind? Similar to upwind sails, you will quickly go from a point of not having enough power to having too much power as the wind speed increases. To complicate things, most racing rules require you to have either jibs or asymmetricals. Furthermore, reaching sails see a variety of both apparent wind angles and apparent wind speeds. In some wind speeds, what is defined as a kite can work if we change the area and shape of the sail, and in stronger winds, what can be defined as an asymmetrical will be too powerful. Lastly, when sailing upwind or downwind, you can find an optimal angle that balances speed with velocity made good (VMG), but when reaching you want to go as fast as possible across the wind toward your next mark or waypoint.

The problem with using downwind sails while reaching is twofold. First, they are fragile because they operate in very light apparent wind speeds, and, second, heavy sails are slow downwind. As you start to reach closer to the wind direction, your apparent wind speed increases rapidly. This also increases the heeling movement sails produce, which is typically the limiting factor determining what reaching sail you can use. Unlike headsails that you can luff, a free-flying headsail, such as an asymmetric, will just flap if you try to sail it too high. If you could fill the sail, it would generate too much side force because it is optimized to drag a yacht downwind, but we want a sail that is more wing shaped and can drive the yacht forward, not backward.

One sail that can cover a wide range of reaching angles is the code zero. While classified under most rules as a kite or downwind sail, it is flat enough to handle points of sail closer to the wind without excessive drag. Because of its wide range of angles, it can be a useful sail for bridging the gap between downwind and upwind sails.

DOWNWIND HEADSAILS

Downwind headsails generally are made for “push mode,” which means they are built with more curve to enhance driving force when sailing with the breeze. Downwind symmetric sails can sail deep angles as the wind is meant to flow into them and then separate and create as much drag as possible, whereas asymmetric kites allow the wind to flow across the sail similar to reaching sails trying to create more lift.

Let’s focus on yachts carrying asymmetrical kites. A downwind sail’s main purpose is to allow a yacht to sail its optimal VMG angle downwind as fast as possible. Similar with upwind sails when ratings are important, you will have a limited area to save rating. Generally, a larger kite will go faster downwind until its geometry becomes too deep and wide. Usually yachts are rated for the optimal area for lighter air kites; heavier air kites are sometimes slightly smaller than you would make in absence of any rules because most yachts spend the majority of their time racing in 12 knots or less. In lighter winds, the best wind angle will always be to sail higher than dead downwind to increase apparent wind speed, which allows the yacht to transfer as much kinetic energy from the wind as possible. By sailing higher angles in lighter wind, you can double your apparent wind speed, which can increase the power your yacht harnesses from the wind by almost four times while only sailing 15 percent more distance.

Now that you have a base knowledge of headsails, ask yourself a few questions: As your apparent wind speed increases and your sail angles tighten, your apparent wind angle decreases. Lighter air kites, with flatter shapes and made of lighter cloth, operate in narrower apparent wind angles and have less apparent wind speed than heavy air kites. As you sail wider angles, optimum depth for your kite increases as the wider apparent wind angle acts to push the yacht, making a deeper sail more efficient. Lighter yachts that sail more across the wind because they can sail faster speeds tend to have flatter kites compared to yachts that are heavier and sail more directly downwind.

- What type of rig and boat do I have?

- What wind speed ranges do I typically see?

- Do I sail in heavy chop on a regular basis?

- How consistent are those conditions (wind speed and chop)?

- Am I concerned with performance handicapping for racing?

- Do I typically sail windward-leeward courses or do I spend more time reaching?

Your answers will dictate what types of sails will best serve you. If you have any questions or would like help making a sail plan, give your local loft a call.