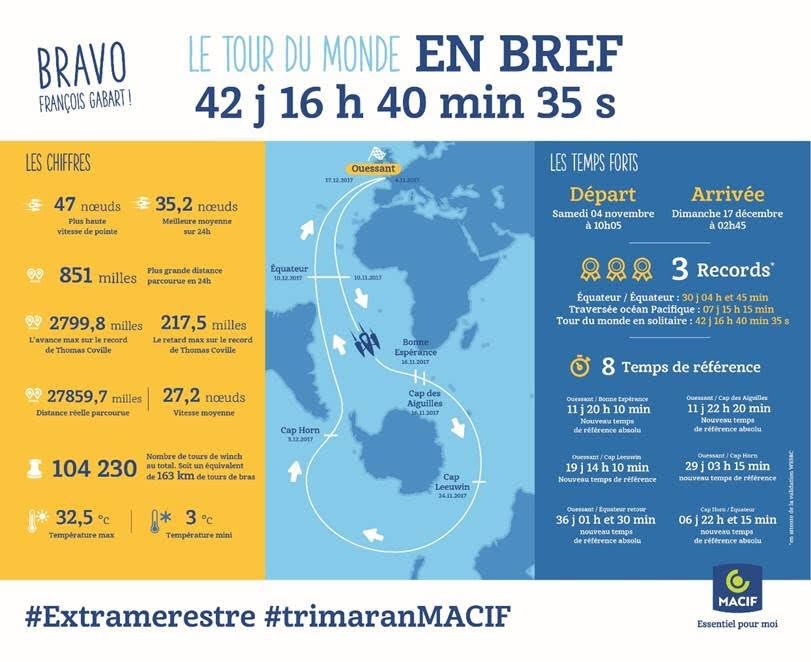

At 34 years of age, François Gabart obliterated – at his first attempt – the singlehanded round the world record. Gabart reduced the previous record by over six days, setting a new standard of 42 days, 16 hours, 40 minutes and 35 seconds. For many, it was the standout sailing achievement of 2017. For some, it's one of the greatest sailing achievements of all time...

From November 4 to December 17, Gabart and his 30m MACIF trimaran covered 27,859.7 miles at an average speed of 27.2 knots. His top speed was 39.2 knots, and his top speed over a 24 hour period was 31.8 knots. Epic!

Gabart was welcomed triumphantly in Brest (FRA) this morning (Dec. 18) and shares some thoughts on this remarkable achievement.

What is your frame of mind as you finish this round the world challenge?

I’m quite simply exhausted and that doesn’t date back to last night. It’s been really hard for weeks. I’m sore all over. It hurts when I raise my arms, but I’m holding out because of the adrenaline and the euphoria.

François Gabart and the trimaran finishes in the port of Brest. – Jean-Marie Liot / Hazard / macif

Droves of admirers turned out to see you in Brest to show you their support. Was this a boost?

I have been literally swept off my feet by the emotion, by their presence, which helped me keep going to the end. To see all these people, all their energy, makes you feel so good, after seeing so few people in the last 42 days. It’s a little hard at first. It takes you by surprise, but it’s wonderful. I am a solitary sailor. It doesn’t bother me to cast off for a few days alone, but I think that deep down I’m a social creature and I need people, so this makes me very happy.

Over these last 42 days and 16 hours at sea, you were occasionally overwhelmed by your emotions, is this because achieving such a performance is particularly hard?

It’s mostly related to the fact that during a record attempt there are things that you accept saying and sharing that you wouldn’t say during a race. Naturally, there are some intense feelings, but the difference is more in the way you communicate them.

I was able to share everything as it changed nothing in relation to the time to be beaten, since, in a way, the competition wasn’t going anywhere. It’s great to sail round the world, and it’s all the more beautiful when you interact with lots of people, who experience what you are living by proxy.

How did it feel to be competing against a fixed time and not other racers?

I really wanted to do this and I found it quite fascinating, because, during a record attempt, you have to push your search for sensations and your understanding of your boat much further.

Another thing that’s different is the way you experience the preparation. With all the training sessions organised by the Finistère Centre when I was preparing a race, it was easy to know where I was and my weak points, so as to progress. However, when you prepare this record attempt, you don’t know where to begin as you are starting with a blank page. This is an interesting approach.

Last of all, there’s the start which is unique. Only you decide, and, believe it or not, it’s not easy, particularly as the choice is a strategic one. It’s powerful from a personal point of view. You can’t prepare yourself mentally in the way you would a race start. You don’t know whether you are leaving on October 22 or January 15.

It’s all very vague. In a few hours, you see the outline of something and it’s action stations for the start of a round the world. This is much more powerful than what happens at the start of races. These are new life experiences and that’s also what I was looking for and what I got.

Were you frightened at any time?

Yes, I was frightened when I saw the iceberg in the South. That took me by surprise. Even though you deal with it, in the hours that follow you say to yourself: “What do you do when it gets dark 4 hours later?” You react passively and fatalistically. You can’t do anything.

What’s more, you’re in the screaming sixties (60° S), an area of the world where there’s nothing if you hit something. If a boat was to come, it would arrive three weeks later. So, I was glad to get away and at the same time, after the event, now that I’m here, I’m delighted I saw an iceberg.

It’s amazing. I always thought that seeing icebergs would be one of the things on my life’s to-do-list, but I was thinking of doing this much later, when I retire, with a good boat in South Georgia. I hadn’t anticipated an iceberg during a record attempt at 35 knots. Fortunately, it turned out okay, but it added to the depth of feeling.

How is the boat doing?

From what I’ve seen, the boat finished in really good condition. We are going to check her out, but I didn’t see anything serious. On the face of it, everything withstood the weather, even though she had one hell of a battering. It was very violent. The boat was built wonderfully well.

Up until this year, we regularly had small problems. I think that we needed two years to test her reliability with a view to a round the world. It was a wise decision to take this two-year approach. I’m really proud of this boat and the work of the team.

It’s just fantastic, as we started out with a blank page. Four years ago, the specifications were to sail round the world as fast as possible singlehanded, with a budget and a launch date, full stop. We couldn’t really go in all directions. We could have built a 50-foot long catamaran. Together with the team we thought things through a great deal. I think we made the right choices.

I work with a wonderful team, as deeply devoted and committed as ever, and extremely meticulous. I share a collective pride with the whole team and with Macif.

Before the start, you said that this record was going to be difficult to beat. You have beaten it by 6 days. Were you being too modest?

I got it a little wrong, but I still believe that this record was difficult to beat. It needed three things to succeed: a good boat, good sailing and a little success. Perhaps there was only one window to set off on this year, on November 4 between 8 and 11 am. This window was not necessarily brilliant at the start, but it turned out to be and I was guided by my lucky star.

After that, I had to keep up the pace and I’m really proud of my circumnavigation. I didn’t make too many mistakes. At the same time, I believe that we can still raise the level of the game and go much faster. And that’s really inspiring. I am reserving this challenge for another time. There’s plenty more to do and to imagine, to sail fast on these boats.

Team details – Tracker – Facebook

Key Milestones from the round the world record

Date of departure: Saturday November 4, at 10:05 (French time, UTC+1)

Ouessant-Equator passage time: 05 d 20 h 45 min

Ouessant -Good Hope passage time: 11 d 20 h 10 min

Ouessant-Cape Agulhas passage time: 11 d 22 h 20 min

Ouessant-Cape Leeuwin passage time: 19 d 14 h 10 min

Ouessant-Cape Horn passage time: 29 d 03 h 15 min

Ouessant-Equator return: 36 d 01 h and 30 min

Equator-Equator passage time: 30 d 04 h and 45 min (new single-handed record)

Cape Horn-Equator passage time: 06 d 22 h and 15 min (new reference time outright)

24-hour distance record: 851 miles (Nov 14, 2017)

Hobie and F18 Aussie supremo Gavin Colby talks Sailjuice's Mike Madge through the techniques for speed in a straight line and speed in the turns..

Hobie and F18 Aussie supremo Gavin Colby talks Sailjuice's Mike Madge through the techniques for speed in a straight line and speed in the turns..