What do all of Paul Elvstrøm’s achievements have in common? Not just the four consecutive Olympic gold medals that the Great Dane won between 1948 and 1960, but the many other innovations he brought to the sport? For example, to name just three, the toe strap, the weight jacket, the self-bailer. Well, maybe he didn’t invent the original Venturi-style bailer but Elvstrøm developed a more user-friendly and more robust version that really became a must-have piece of equipment for every dinghy and small keelboat sailor.

Everything he did was about making the boat go faster, whether it was focusing on his own human performance, introducing a toe-strap to the Finn where, up until then, even the best sailors were content to sit on the side-deck. Perhaps there are times when you and I wished that Elvstrøm hadn’t dreamed up this now ubiquitous instrument of torture! And when everyone started copying his toe-strap and hiking for themselves, he made a hiking bench so that he could practise sitting out for minutes at a time in the discomfort of his own home. Not content to stop there, he later introduced the weight jacket which, thankfully for most of us lesser mortals, was banned from sailing in the mid-nineties.

When you challenge convention as vehemently and consistently as a Renaissance Man like Paul Elvstrøm, a man who never settled for the status quo, you’re bound to ruffle a few feathers along the way. When asked what were his favourite wind conditions, Elvstrøm would reply with a wicked grin: “A storm.” And to prove his point he’d head out into the teeth of near-gale force conditions on the day before a Finn Gold Cup, merrily gybing the boat and standing up between manoeuvres, making mincemeat of the boathandling and perhaps more importantly, making mincemeat of his competitors’ nerves as they stood on the shore, watching in awe at a legend in the making. It wasn’t just his boathandling that was light-years ahead of the opposition of his game, it was everything else too.

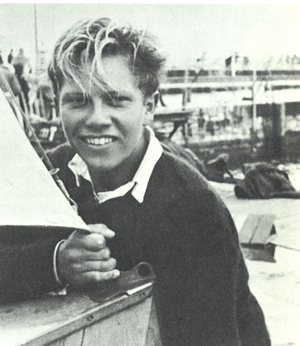

Elvstrøm first shot to prominence at the Olympic Regatta for the London 1948 Games, when the sailing took place in Torbay. The young Dane, barely out of his teens, went there with low expectations and didn’t start well either. But he learned and matured rapidly throughout the regatta. With two races to go he had a shot at winning, although Elvstrøm would have to win both races. The breeze was gusting hard and sailing the Firefly singlehanded with main and jib, the young sailor didn’t have the weight advantage of his rivals. But, ever the innovator, he sailed the upwind legs with mainsail only, and hoisting the jib on the downwind legs for extra power. While his rivals capsized, Elvstrøm stayed upright and sailed to a surprise gold, making him an overnight sensation in Denmark.

It was the start of great things, with Elvstrøm going on to win the next three Olympics in the Finn singlehander. But with every success, it took more and more out of Elvstrøm in his quest for ever greater levels of perfection. It reached the point where he used to be physically sick before races, and eventually the psychological torture became so great he withdrew from the sport for more than a decade.

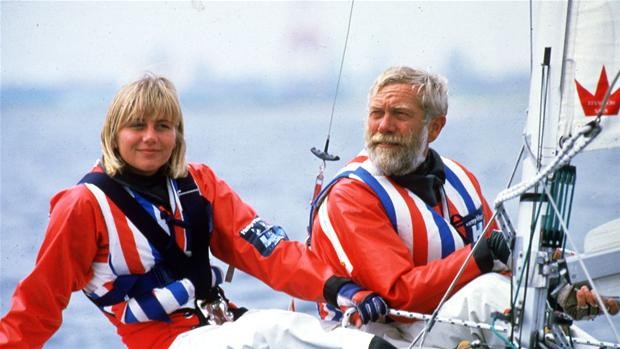

Fortunately for him and the sport, Elvstrøm found a way back into the sport that allowed him to enjoy sailing again, and still perform at a very high level even into this fifties and early sixties when he competed for Denmark in the Tornado at the 1984 and 1988 Games crewed by his daughter Trine. Depending on the wind conditions, Paul or Trine would take it in turns to get on the trapeze (this was back in the days when the Tornado was a single-trapeze catamaran without gennaker).

Where helming from the trapeze today is fairly commonplace, Elvstrøm was forced to take this on at the 1966 505 World Championships in Australia when his regular crew was ill. The Dane recruited a local young sailor, Pip Pearson, to become his replacement forward hand, but Elvstrøm being the heavier man, it made sense for him to steer from the trapeze. Together, the newly formed team finished second at those Worlds.

Elvstrøm’s quest for speed manifested itself in his development of a singlehanded trapeze boat called the Trapez which competed in an IYRU (now World Sailing) trial for a new boat in 1965. Although it was fast, it was widely thought to be too complex and was not widely adopted, while Ben Lexcen’s version of the same concept, the Contender, proved more successful. Still, Elvstrøm was always looking to the next thing to make boats go faster and he must have marvelled at the foiling developments of recent years.

Elvstrøm’s legacy can be found in almost every part of the sailing world, from the books that he wrote to the global network of sail lofts that bear his name. Gary Jobson offers some great insights and memories of Elvstrøm, which you can read here.

If there’s one thing that we can all learn from the master, is never to accept the status quo, to believe that just because that’s how things have been for a long time is a justification for how they should be tomorrow. His ability to see past the limitations of the day and always to demand more of his body, mind and equipment, that’s what made Paul Elvstrøm such a special talent.